|

Rabindranath Tagore. Drawing by Satyajjt Roy

The Parrot's Training

Introduction

This unusual story drives home its message by a kind of literary reductio ad

absurdum. It is a satire, full of wit and sarcasm, and can be regarded as a preface to

a revolution in education.

Rabindranath Tagore dreamed of creating a garden of learning where children

would command the centre of attention. During his own school days he had

experienced the deadening effects of the formal system of education, and his soul

had rebelled against its imprisonment within school walls. He ultimately rejected the

school and educated himself, and he discovered a teaching-learning process

governed by freedom and ever-increasing intimacy with nature —physical, human

and divine.

In 1901, Rabindranath Tagore established a new school at Shantiniketan, a

school without walls. It was to be a place where children would be free to live under

the canopy of the sky and listen to the wind and the birds. Tagore maintained

that 'here is an inherent harmony between man and nature and that man can learn

from nature by an intimate friendship with it. Tagore also conceived of his school as a

place where teachers and students would live together, as in the ancient Gurukulas

"'India. When teachers and students live together, they learn from each other;

the growth of the pupil is intertwined with the growth of the teacher. In Indian

terminology, a school has to be an "ashram", and Rabindranath Tagore looked

upon Shantiniketan as an ashram.

Tagore was a true teacher, rightly known as Gurudev, since he placed children

Page-303

in the centre of his ashram and put himself at their disposal. He interwove his own

life with the life of the ashram children. He wrote plays which were staged at

Shantiniketan, and himself played different roles along with the students. He wrote

innumerable songs and poems and composed incomparable music that can be a

perennial source of inspiration and awakening to the inmost soul. Tagore's deepest

interest was to bring out the mystery, wonder and delight of the human soul's

yearning to unite with the divine, and he attempted to give a concrete shape to this

interest in the setting and rhythms of life of Shantiniketan. Tagore's was a

revolutionary experiment in education and like every revolution it had modest

beginnings. Although there was rough weather throughout the course of its

development, there was a widespread appreciation of the attempt. Several leading

teachers, such as Nandalal Bose, C. F. Andrews and W. Pearson, joined him in his

unusual experiment.

In 1913, Tagore was awarded the Nobel Prize for his famous book Gitanjali.

Thereafter he was invited to visit many foreign countries where he often spoke of his

school and its experiments. As a result, a large number of people came to know and

understand the significance of his educational revolution. Indeed, his revolution was

unusual for it involved not war, but peace. The very name of the school,

Shantiniketan, means the abode of peace. He also named his school "Vishm

Bharati" to emphasize international understanding and the universality of man. And

he selected for Vishwa Bharati the motto, "Yatra Vishwam Bhavate Ekanidam" —

"Where the world makes its home in a single nest. "

Rabindranath Tagore declared that Vishwa Bharati was open to all who wanted

to live together in the spirit of universal fraternity. He wanted Vishwa Bharati to be

a living symbol of a new life that would foster world citizens not bound to any

narrow affiliation. It was to be a setting of the complete life of man, and he saw

interconnections between the life of his ashram and the neighbouring villages. He

realized the importance of rural development and the contribution education can

make to it. To give a concrete shape to this perception, a special wing was added to Vishwa Bharati under the name of "Sriniketan ", and Tagore emphasized the need to

integrate both Shantiniketan and Sriniketan in a close bond.

In 1951, ten years after Tagore's death, Vishwa Bharati was given the status of

an Institution of National Importance by an act of Parliament. Since then it has

become a Central University. However, its revolutionary character was diluted and

it began to be run on lines not very different from the other universities in the

country. In 1984 a comprehensive amendment to the Vishwa Bharati Act was carried

Page-304

out, and it is expected that, with

some new features that emphasize

innovations in education, the

university might be able to recover

something of the original idea that

Gurudev strove to realize. The

experiment of Vishwa Bharati

presents to us many lessons which

can be useful in any new

educational experiment.

Tagore saw no opposition

between the humanities and

science, no conflict between science

and spirituality. Even as he wrote

great poetry and composed unusual

music, in the latter part of his life he

gave his students and teachers an

instructive book on the science of

the universe, Vishwaparichay.

Tagore was a great poet and

artist, a great philosopher and

humanist, a great teacher and student.

Through all his works and activities he studied the mysterious and multi-coloured personality of man and he emphasized the

truth that education should be a free and joyous growth of faculties and capacities

so as to develop a harmonious personality in the learner.

Page-305

G.N. Chaturvedi, Auroville.

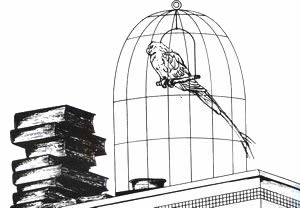

Once

upon a time there was a bird. It was ignorant. It sang all right, but never

recited scriptures. It hopped pretty frequently, but lacked manners.

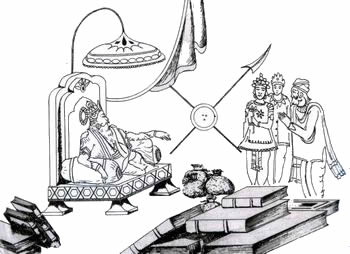

Said the Raja to himself: "Ignorance is costly in the long run. For fools,

consume as much food as their betters, and yet give nothing in return."

He called his nephews to his presence and told them that the bird must have a

sound schooling.

The pundits were summoned, and at once went to the root of the matter. They

decided that the ignorance of birds was due to their natural habit of living in poor

nests. Therefore, according to the pundits, the first thing necessary for this bird's

education was a suitable cage.

The pundits had their rewards and went home happy.

A golden cage was built with gorgeous decorations. Crowds came to see it from

all parts of the world.

Page-306

"Culture, captured and caged!" exclaimed some, in a rapture of ecstasy, and

I burst into tears.

Others remarked: "Even if culture be missed, the cage will remain, to the end,

a substantial fact. How fortunate for the bird!"

The goldsmith filled his bag with money and lost no time in sailing

homewards.

The pundit sat down to educate the bird. With proper deliberation he took his

pinch of snuff, as he said: "Text-books can never be too many for our purpose!"

The nephews brought together an enormous crowd of scribes. They copied

from books, and copied from copies, till the manuscripts were piled up to

an

unreachable height.

Men murmured in amazement: "Oh, the tower of culture, egregiously high!

The end of it lost in the clouds!"

The scribes, with light hearts, hurried home, their pockets heavily laden.

The nephews were furiously busy keeping the cage in proper trim.

As their constant scrubbing and polishing went on, the people said with

satisfaction: "This is progress indeed!"

Men were employed in large numbers, and supervisors were still more

numerous. These, with their cousins of all different degrees of distance, built a

palace for themselves and lived there happily ever after.

Whatever may be its other deficiencies, the world is never in want of fault-finders; and they went about saying that every creature remotely connected with the

cage flourished beyond words, excepting only the bird.

When this remark reached the Raja's ears, he summoned his nephews before

him and said: "My dear nephews, what is this that we hear?"

The nephews said in answer: "Sire, let the testimony of the goldsmiths and the

pundits, the scribes and the supervisors, be taken, if the truth is to be known. Food

is scarce with the fault-finders, and that is why their tongues have gained in

sharpness."

The explanation was so luminously satisfactory that the Raja decorated each

one of his nephews with his own rare jewels.

The Raja at length, being desirous of seeing with his own eyes how his

Education Department busied itself with the little bird, made his appearance one day

Page-307

G.N. Chaturvedi, Auroville.

at the great Hall of Learning.

From the gate rose the sounds of conch-shells and gongs, horns, bugles and

trumpets, cymbals, drums and kettle-drums, tomtoms, tambourines, flutes, fifes,

barrel-organs and bagpipes. The pundits began chanting mantras with their topmost

voices, while the goldsmiths, scribes, supervisors and their numberless cousins of all

different degrees of distance, loudly raised a round of cheers.

The nephews smiled and said: "Sire, what do you think of it all?"

The Raja said: "It does seem so fearfully like a sound principle of Education!"

Mightily pleased, the Raja was about to remount his elephant, when the fault-finder, from behind some bush, cried out: "Maharaja, have you seen the bird?"

"Indeed, I have not!" exclaimed the Raja, "I completely forgot about the bird,"

Page-308

Turning back, he asked the pundits about the method they followed in

instructing the bird.

It was shown to him. He was immensely impressed. The method was so

stupendous that the bird looked ridiculously unimportant in comparison.

The Raja was satisfied that there was no flaw in the arrangements. As for any

complaint from the bird itself, that simply could not be expected. Its throat was so

completely choked with the leaves from the books that it could neither whistle nor

whisper. It sent a thrill through one's body to watch the process.

This time, while remounting his elephant, the Raja ordered his State Earpuller

to give a thorough good pull at both the ears of the fault-finder.

The bird thus crawled on, duly and properly, to the safest verge of inanity. In

fact, its progress was satisfactory in the extreme. Nevertheless, nature occasionally

triumphed over training, and when the morning light peeped into the bird's cage it

sometimes fluttered its wings in a reprehensible manner. And, though it is hard to

I believe, it pitifully pecked at its bars with its feeble beak.

"What impertinence!" growled the kotwal.

The blacksmith, with his forge and hammer, took his place in the Raja's Department of Education. Oh, what resounding blows! The iron chain was soon

: completed, and the bird's wings were clipped.

The Raja's brothers-in-law looked black, and shook their heads, saying: "These

birds not only lack good sense, but also gratitude!"

With text-book in one hand and baton in the other, the pundits gave the poor

bird what may fitly be called lessons!

The kotwal was honoured with a title for his watchfulness, and the blacksmith

for his skill in forging chains.

The bird died.

Nobody had the least notion how long ago this had happened. The fault-finder

was the first man to spread the rumour. The Raja called his nephews and asked them: "My dear nephews, what is this

that we hear?"

The nephews said: "Sire, the bird's education has been completed."

"Does it hop?" the Raja enquired.

"Never!" said the nephews.

"Does it fly?"

"No."

Page-309

"Bring me the bird," said the Raja.

The bird was brought to him, guarded by the kotwal and the sepoys and the

sowars. The Raja poked its body with his finger. Only its inner stuffing of book-

leaves rustled.

Outside the window, the murmur of the spring breeze amongst the newly

budded asoka leaves made the April morning wistful.

From

Boundless Sky (Calcutta:

Visva-Bharati, 1964), pp. 84-88.

The following is a list of a few selected works by Rabindranath Tagore with the year of their first

publication:

Poetry

Gitanjali (1910), Lipika (1921).

Drams

ValmikiPratibha (1881), Achalayatan (1912),

TasherDesh (1933), Nrityanatya

Chitrangada (1936).

Novels

ChokherBali (1903), Gora (1910),

GhareBaire (1916), Shesher Kavita (1929).

Essays

Manusher Dharma (1933), Visva Parichaya (1937),

BanglarBhasha Parichaya (1938).

Memoirs and Letters

JivanSmriti(1912).

Biography

Rabindranath Tagore was born on 7 May 1861 (Vaisakh 25, 1268 according to the Bengali

calendar). A clear picture of his early days emerges in his Story of My Childhood, written a half-century later. He began writing prose and verse in his mid-teens.

Page-310

Morning Songs, the first notable landmark in his poetic development, had already been preceded

by a dozen slim volumes. The young poet then turned to drama.

Out of an immense exuberance that had to find an outlet, verses came in scores, in hundreds,

amazing in their variety of form and rhythm and in imaginative vigour. The period of youthful

dedication to the spirit of beauty passed presently into mature contemplation and philosophic

profundity. Next came the Gitanjali phase and the poet rose to world stature. The Nobel Prize

award followed in 1913.

The quantity of his output was immense. He wrote more than a hundred volumes of poetry and

plays, but the range and variety of his production were no less astounding. There were many

novels, short stories, essays, philosophic and aesthetic treatises (mainly addresses delivered in

India, Great Britain and the United States), travel diaries and even textbooks for children. Among

the most significant of his works were his songs, the number of which ran into four figures. Set to

music, exquisite in imagery and sensitiveness, these songs are today an integral part of the cultural

life of Bengal. When well over sixty, he took up painting and evolved a highly personalized

technique. Collections of his paintings exhibited in Paris and elsewhere drew warm appreciation

from the foremost critics.

His lifework, however, was not confined to the arts. He was a great patriot, though not a

politician. He was resolved to work not only for a co-ordination between India's past and present,

a fusion of the best elements, but also for a synthesis of the East with the West, a "union" between

them. The world outlook of Rabindranath Tagore drew eager response from Europe's great writers

and philosophers, and Remain Rolland voiced a common feeling when he stated that the Indian

poet had "contributed more then anyone else towards the union of these two hemispheres of the

spirit."

In 1901, he started a school at Santiniketan. Later the time came for the fulfilment of the poet's

dream of a "World University." In December 1921, Viswa Bharati was formally inaugurated.

Whoever came in contact with the personality of Rabindranath Tagore, even for a brief space,

received one predominating impression — that of richness. It was a richness of the spirit and was

not limited to genius. There was the superb charm softening the intellectual blaze; the innate

simplicity belying the sophistication, but, above all, the never-failing humanity with which the poet

made his forceful impact on all levels of awareness.

Based on Bhabani Bhattacharya, Introduction, in Rabindranath Tagore, The Golden Boat

(Bombay: Jaico, 1985), pp. vi-ix.

Page-311

|